It wasn’t officially declared a war zone when I got to Hong Kong. Not yet. But it wasn’t far off.

It’s why I decided to go in the first place, visit the frenzied and forlorn city instead of trekking the jungles of Laos.

I had jumped in just before the powderkeg weekend that would juxtapose the 5th anniversary of the Umbrella Revolution with the 70th birthday of Communist China. Something would go down, everyone knew, but what, and when, and how big was anyone’s guess.

I was just a two-hour flight from finding out for myself. Screw it, I thought. The jungle can wait. Can I say the same for the civilized world?

When I first stepped off the plane, it took a moment to shake off the dust of ten weeks in Vietnam. Things were different here. They whizzed and flashed and screamed for attention and moved without asking, all sterile poetics.

That frenetic pace is the lifeblood of Hong Kong, a Big City with Big Plans, powerful piston of capitalism that keeps Red China rolling.

I had come for the first-hand Civics lesson but didn’t know where to look for it, so I went searching for answers with the other students at Hong Kong University.

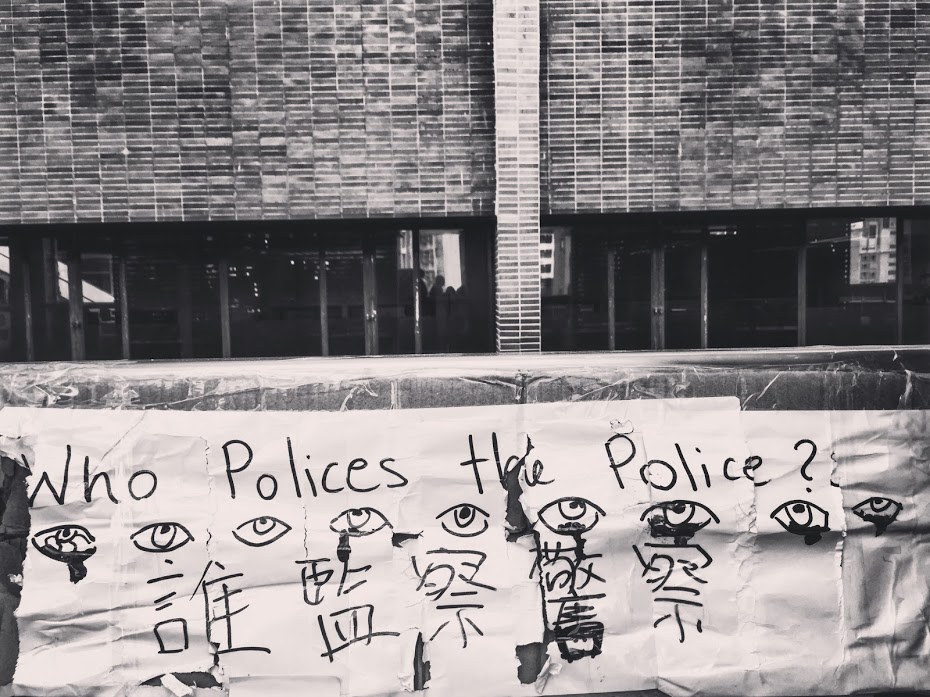

The city’s superb subway system delivers you directly to campus and straight into the heart of the movement: a mosaic of post-its and posters and cardboard scraps splashed with English and Cantonese, pleas for peace and destruction, strange symbols of budding revolution, Winnie the Pooh and Pepe the Frog and Guy Fawkes and gas masks and bloody eyes and raised fists. The floor is reserved for political mugshots, where visitors can tread on the face of the powerful.

As I took it all in, a student took it upon himself to add to the exhibition, spray-painting a long Cantonese credo in front of a ghastly depiction of Tiananmen Square. Curious, I asked a fellow onlooker if he knew what it meant.

‘The first part explains his thoughts on China,’ he said, ‘The last two lines say “Liberate Hong Kong. Revolution of our Times.”’

A popular slogan, screamed in the streets and shouted on the walls, it had roots in the Umbrella Revolution of 2014, doomed peaceful movement when Hongkongers last made their demands against China known. Its method was occupation, its symbol adopted from one small act of defiance: a councilman daring to open an umbrella at a ceremony honoring the 65th anniversary of the People’s Republic. Nylon yellow call to arms, it ushered in several months of nonviolent revolt. But the sit-ins couldn’t stand up to sustained police intervention, and the People never fully forgave the Force for their role in snuffing things out.

My fellow observer colored this context for me until we caught up to the present, social shades of grey and all the psychological underpinnings this time around. It took hours and we’d barely begun.

But nevermind all that, there would be time for history later. For now, there was a demonstration to get to: a rally for victims of police brutality. They’d be speaking out tonight, in Edinburgh Place, just downtown. Would I like to go?

The event had received the rare blessing of Hong Kong police, so the act of being there wouldn’t be considered a crime. Still, there were a few things to know before going.

Hongkongers have a phrase to describe their demonstration approach: ‘Be like water,’ a nod to the Daoist concept of The Way, a reminder to take to the streets with inherent flow. It means the action stays fluid, breaking gladly against any damming scenarios. No resistance. The crowd simply moves where it will.

Tactically, this keeps police on their toes too, tiring a competitor that far outpaces the movement when it comes to training and weaponry. Emotionally, it keeps rather cool blood pumping through a potentially wild heart. As long as you stayed present and kept moving, my new friend told me, you’d be alright.

‘But you can’t really understand it until you experience it,’ he added. ‘Did you happen to bring your own gas mask?’

Before things got started, my new friend and I went on a quick tour of Kowloon, stopping for toast and eggs at a locally-famous establishment.

How easy it was in those moments to believe this was just another night in a new city. The streets hummed with neon. Buyers bought. Sellers sold. People got about their Fridays at an urban clip. Inside the restaurant forks scraped on plates. Bills tallied. Orders rang. Kitchens buzzed. Remarkable normalcy, one could stay lost forever in the stainless steel shine.

But just a few blocks away under overpass shadows was the Mong Kok Memorial, standing tribute to the movement’s respect and suspicion. Blossom of violence, it was erected on behalf of three protestors widely believed to be killed during a late-August clash with police. The department denies these claims but also refuses to release the surveillance footage that would put them to rest. The best-case scenario, many Hongkongers believe, is that the three have been Disappeared.

On the far side of the monument, under vigilant candlelight, is a running tally of protestor suicides reported since June. The figure has climbed high enough to raise more than a few suspect eyebrows.

And just 10 minutes by subway was the night’s Big Event. The victims would speak of abuse they saw and suffered through at the city’s most notorious prison, the only one in town without CCTV, where more protestors were reportedly being detained due to ‘space issues’ at the handful of half-empty jails closer by.

The rally was a sea of black, the color of protest, and the sparkling stars of 50,000 lights lifted as One. The new Hong Kong anthem played and bounced off the walls of towering industry, echoing deep through the canyon of wealth. The twinkling black tide chanted and made its demands known. Autonomy. Freedom. Justice. When it came time for the speakers, every person sat down, listening with a quiet as intense as their rally cries.

It had been a peaceful success. Afterward, all anyone wanted to know was why.

Where were the police? Were they lying in wait? Or just waiting for later?

There were plenty of chances for clashes this weekend. Would they strike harder during tomorrow’s Umbrella Movement anniversary? Or Sunday’s March Against Totalitarianism? Surely they couldn’t strike hard against both. (Or could they?) Too much violence would just encourage too many more to join the movement. (Or would enough force quash momentum?) But surely, surely they’d have to do something. This weekend was far too important for China to lose any face.

Hong Kong’s foundation of resistance is built on this miracle of cumulative guesswork. In the long, fine Asian tradition of collectivism, it rests its strength on the masses, producing, through sheer force of will, an astonishing leaderless gameplan.

AirDrop and Telegram and Twitter and Whatsapp send digital smoke signals and word of mouth does the rest. Revolution of Our Times, indeed.

It all functions as impressive thoroughfare, but along the way the route twists with rumors, and any government response is an untrusted detour. All the keen instincts of paranoia keep the thing gassed up through the ricochet switchbacks of Revolution.

The only thing anyone seemed to be sure of that night was that Tuesday would not be good. The National Day of the People’s Republic, and the new nation’s 70th birthday to boot.

A military procession befitting the grand round number was on tap for the streets of the capital. The last thing Beijing would want was for the island ruckus to rain on its martial parade. But most Hongkongers had their umbrellas ready.

Saturday night and my heart is pounding. I’m on my own, not too far from the front line at Admiralty.

Would tonight be the Big One?

It was the Umbrella Revolution anniversary party and everyone was waiting for the guests of honor to arrive. The protest started at seven. The police, everyone seemed to know, somehow, would be there by nine.

The venue was the first scene of the original movement, a brutalist government complex buttressed by an MTR station and a wide swath of highway, tangled seam of overpasses and tunnels keeping the sprawling site stitched together. It was empty of the familiar grey suits of daylight. All that remained were the ones dressed in black.

The scene was quiet save for some small sounds of destruction, ringing hammers on metal and brick, sidewalks and fences being pillaged for city-funded fortifications. It tolled like a bell keeping uneasy time.

I looked at my watch. Three minutes to nine. Were our police friends the type who arrived early, or fashionably late?

I’ve been shaken before, physically shocked into submission, but this was something new. Never had the potential for violence existed so far outside of myself. It gave the terror free run of my imagination: nervous anticipation, an unseen circling Jaws, movie monster known only through the fear in the eyes of its victims.

A sick thrill, I thought in those eerie quiet moments of approaching dissent. That roiling stomach condition you love so well. Fuck. This isn’t even your fight. What are you doing here? These people are willing to bleed and burn and die for this. Are you willing to do the same?

It was just then a courteous protestor interrupted my queasy thoughts.

‘The police are coming now,’ he said. ‘The front line is just there. You need to get safe.’

And suddenly there they were, faster than rising panic, a wall of black riot gear, heavy helmets and bulletproof shields. They waved the Red Flag: Stand down, or we will charge. The front line bucked at the sign like angry bulls.

‘Murderers!’ they taunted in Cantonese. ‘Gangsters of the State!’

The hacked up fences, traffic cones and other junk spilled across empty streets, obstructing the path to pursuit. Things got louder. The flag switched from Red to Black: A warning, I had learned, that the next move was teargas.

It came in billowing waves. A few booming shots and a smoky flood of chemical pepper, a sting that stuck in your throat and made you well up despite yourself. Running from it only meant sucking it down harder.

‘Know your exits,’ my friend from the university had told me the night before. And before the party started that night, I had studied them well.

Many fled at the first familiar sound of doom. I darted with them through the station’s worm tunnels, emerging at a safe space where I could observe the action through bleary eyes at a breathable distance.

The hardcore frontline held firm while the police were busy preparing their next trick: the firehose loaded with capsicum-laced water and spiked with blue dye, anointing protestors with burning skin and an easy mark.

The fight didn’t last long after that. The frontline gave the signal to fall back, be like water, disperse.

I didn’t feel like water. I felt like cold sweat and burnt lungs. All the demented excitement of cats and mice. A chewed up raw nerve of adrenaline.

In the end, seasoned protestors told me, the rally didn’t amount to much. They would come hard tomorrow, it was decided. Tonight was a warm-up round. Get your rest.

You can hardly run into anyone in Hong Kong these days who doesn’t have a tale of brutality. And their stories all follow the same basic arc: I was doing nothing wrong. Walking too close to a protest, maybe. The wrong place at the wrong time for sure. And then there was pepper spray, forced searches, sharp questions.

Anything perceived as evidence can and will be used against you.

These stories came to me from everywhere, people who bled for the movement and people who barely cared. Eager young faces born into dissent, waiting to catch frontline action, hold the police accountable for crimes from before their time. Grizzled expats reading graffiti prophecies, bleakly speculating when The Money would flee and send the whole island to its knees. Mothers and fathers and grandparents, wondering how much more the People could take.

This disillusioned tessellation of faces packed the street by the hundreds of thousands the following day. The March Against Totalitarianism, a demonstration much different than ones I’d seen in the states.

There were hardly any clever signs begging to stand out. The crowd instead thrived as one: All in black; all carrying umbrellas; all towing the line.

Fight for freedom! Stand with Hong Kong! the streets sang out in a thousand-part harmony. The tenor of the words rang deep in my bones. I had been wrong the night before. This was my fight. This was everyone’s fight. Justice. Liberty. Equality. What else in the world mattered?

I stopped to rest a minute the mangled ankle and broken toe I’d brought with me from Vietnam, gift of speed and steep switchbacks and stupidity on a motorcycle ride a few weeks earlier. I sat down next to two girls. They were 16 years old. Dressed in black. Faces swaddled in paper masks.

They spoke to me in words beyond their years about the power of protest, the free future they hoped for, the fraying ties with police. Did I know they said up to 20 percent of police actually wanted to quit? They were too scared to actually do it though. There was a lot to be scared of nowadays.

They asked if I’d be okay on my bad ankle. They told me they had to be home in time for dinner or their moms would be worried.

As the movement passed by, they sketched out for me its finer details. Communication was stunning and simple: a signal for stop, one for go, one calling for medics. Human chains stretched vital gear down city blocks, one pair of hands at a time.

When police make a move and the front line backs off, the crowd begins chanting: Yhut, ngee! Yhut, ngee! ‘One-two! One-two!’ It keeps a steady pace of retreat, keeps the panic in check, keeps each other away from a sad trampled end.

I understood then what my friend had said about the movement’s intrinsic mechanics of zen. Everything flowed, effortless. Float the river of dissent on the raft of the masses. There’s no need to panic. They can’t be bigger than all of us. We are Water. Mighty force that’s turned so many mountains to mud.

But the storm’s backend soon collapsed on its sweet eye. Chaos. The police were here. Somewhere, we sprung a leak.

The girls had gone home for the night, safe, I hoped, on their way back to dinner. I was standing on top of a highway median, watching the major arteries of a major city blocked up with a thousand black cells. And soon they were rushing past, throbbing heartbeat of a movement in retreat from the promise of pain and detention.

In that moment, there is only room for instinct. Scatter. Slide. Sprint. The hoses were out. The booming guns sounded, first tendrils of teargas snakes.

Put your mask on. Find your exits. Run. Run. Run. Turn left. No. Cut right, hop over the fence. Back into the street. Hands waving wildly, calling for medics, signaling police positions, sharing news down the line. Yhut, ngee! Yhut, ngee! The pacing cry was delivered at a gallop.

Fearsome front liners held their ground, and tonight they were ready, matching brutal outbursts with their own firepower. All teargas waltzes and firebomb sprints, the streets exploded with Molotov cocktails and a hailstorm of bricks.

I had no helmet, no press vest, no gasmask. I fled for cover in the nearby district of Wan Chai, old Westerner haunt where the gweilo went looking for Hong Kong’s darkest corners and cheapest thrills.

Soaked with sweat and pouring tears, I stowed myself inside a Mexican restaurant, horribly thankful for the color of my clothes, the color of my skin, the assimilation and all its presumed innocence.

The Rugby World Cup was on. The A.C. was pumping. The clientele were drunk. The game was news. The protest was noise.

A few mildly curious customers pulled away from their margaritas long enough to eyeball my entrance, and one or two even wandered over to the door. Hongkongers clad in black were running from something. Running from what? Why was everyone around here so goddamn edgy?

Eh, who cares. Another try scored! Another round, waiter. More salsa and chips.

The violence stretched long into the night. Entire streets were hacked apart. Vengeful and brutal writing on the wall. Thudding bricks on police car roofs and teargas shots and angry shouts.

Down the way, some small fires burned. But waking up Monday, you’d never know.

Accustomed to the fierceness of natural storms, the stuff man can come up with is nothing for Hong Kong streetcleaners. Sidewalks were restocked with tomorrow’s brick weapons, fires reduced to ash marks, posters peeled away, all in a matter of hours. Only the graffiti remained, and the heavy dust in the air.

Hongkongers went to McDonalds and went to Mannings and went to work, dressed in white and dressed in colors. The subway ran, its impartial hum carrying students and store clerks, bankers and lawyers, baristas and teachers and stay-at-home moms and me.

Tomorrow was The Big One. But today was therapy. Today was needed. I ignored the writing on the wall with all the rest. I wore flip flops. I did tourist things.

How easy to hide in the comfortable patterns of waking and working. A great invisibility cloak of the mind. Perhaps this compartmentalization was all part of it: A reminder of the peace on the other side, dull droning societal serenity worth a revolution.

Or maybe it all boiled down to divine denial. Surely, such ire was hardly sustainable. Maybe the trick of prolonged rebellion is keeping it in the calendar margins of nine-to-five.

Many have spoken of this movement as an Example, and I began to understand then the many ways in which that was true. Hong Kong was a nation of Weekend Warriors. A strange syncopated step keeping perspectives in check and full-on war at an arm’s length.

Demands could be listed and grievances aired, but the Ship of State sailed on, buoying all with some small sense of security.

Maybe this, too, was Being Water.

Whatever the cause, I was grateful. Calm enough, even, to indulge a bit.

There had never been a better time in my life for yoga. Luxury of release for mind, body, and soul, a few stretches, bends, folds in the corner of my tiny room, an emancipation of anxiety and raw nerves and doubt.

My own moment of Being Water, finding, once again, a personal flow. Recenter. Breathe. It’s going to be okay. All you have is this moment. And all you can do with it is the best you can.

Priceless gift of the universe, free energy to manifest as you please. And tonight, I choose to manifest peace.

But it was short-lived. Tuesday’s alarm was the sirens. Just a precaution, distribution of fire trucks down the line.

The day had already been called high advisory. From a meteorological tilt, heavy pollution would stifle the air.

No relation to the heavy vibrations of protest. It was a National Holiday, the 70th Anniversary of the People’s Republic.

Nearly everyone had off, free to watch the whole showy parade on TV if they wanted. But the real action would hit much closer to home.

The demonstration officially started at one, but the MTR had been shut down that morning, keeping all movement to the island a highly-monitored nuisance. The Water sprung up instead in a wellspring, pools of protestors burbling dissent all over both sides of the Harbor.

I was there in the heart of Hong Kong. As the fates would allow, my hotel sat snugly on the parade route du jour, just between Central and Admiralty, the city seats of financial and government power.

I had a window seat to revolution, two stories up. Not that I used it. Not at first, anyway.

The previous day I’d acquired a gas mask, gift from a fellow reporter, though they were sometimes on offer from protestors too. Funny fluid currency of the Hong Kong free market. It helped me breathe easier. I stuffed it in my bag and met my University friend for lunch.

A strange diner scene, far different from my first night in town. Protestors streamed past the window, staring in at the zoo. We stared out, sipping last-minute tea at one of the last places open in town, a rendezvous point for another friend on his way.

Conversations with other trapped diners filled the tense lull. We all knew what was coming. Knew and didn’t know. How bad would it be?

‘If they had only given us what we wanted at first…’ an elderly patron began. ‘But it’s all too late for that now.’

Those fatalist drifts seemed to seize the whole city. No one was willing to predict how this thing would end, but no one was betting on Peace.

My new friend’s friend arrived then and we plunged back into the scene. The flow was a bit quicker, but steady. The movement pressed on.

Paper money littered the wind, a traditional offering for the recently dead. It symbolized the passing of the Power of China.

A few black flags waved. A few black-clad protestors snuck off to cover the street with more posters. A few preferred spray paint.

‘We’re not vandals, we’re artists,’ one t-shirt proclaimed. ‘Expect victory and you make victory,’ another read.

‘Ideas are bulletproof,’ the walls declared. ‘Break the System. Free Yourself.’ ‘Fuck Chinazi.’ ‘Never forgive. Never forget.’

My new friend’s friend had seen this before. He was there in 2014, the thick of it. He hadn’t forgotten.

‘Five years ago, we thought we had to justify the means,’ he said, voice muffled under paper mask. ‘Now all that matters is achieving the goal.’

Shifting tides of sentiment had pulled protestors to one of two poles, he explained: the more peaceful movement, called the Central Gang, who preferred the Umbrella methods of sit-ins and civil disobedience; and the Mong Kok Gang, frontline fighters who saw increasingly fewer problems with returning shots fired.

The groundswell was behind the latter group, or at least generally trending toward radicalization. Even those dedicated to armistice had become frustrated at its limited outcomes.

‘We saw our peaceful methods fail last time,’ my new friend’s friend, a member of the Central Gang, said. ‘And they react to the violence. When one million people come out in the streets and the government does nothing, then two million come out and still nothing. What more can you do?’

But the kind of attention attracted by violence has a funny way of doubling down on itself. We had been walking back West, back toward Admiralty, when the signals flared. Police ahead. Fall back. Yhut, ngee. Yhug, ngee. Then, from behind: police spotted, too. Water cannons and tear gas guns on both fronts.

Trapped. We had been funneled straight into an impossible well. Panic. What good is knowing your exits when you’ve been surrounded? We may have been water but they were a moat.

A frenzied sprint broke out in every direction. Frontliners fell back to defend every flank. Those caught up in the middle scrambled for hope of open cafes, Circle Ks, alleyways – anywhere a person could hide and ride out the fury of a passing police storm.

My hotel was just a few blocks away. I grabbed my new friend and his friend in the madness and we started to run.

‘Stick to the walls,’ one of them shouted. ‘You’ll have at least one side covered that way.’

We dodged flailing bodies and barricades, rounded tight corners, hopped fences, slid through shoving waves of fear. The final dash was teargas frogger, one last sprint across the riptide of a seven-lane ocean. We set eyes on the target and took a deep breath. We made it inside just before the bombs went off.

Upstairs in the air-conditioned lobby, we watched the world burn. The bay windows lent themselves to the awesome view.

A battering ram of riot police brutalized the street. Frontliners backpedaled but didn’t retreat. The two fronts collided just outside the hotel. The air exploded with assault on both ends. Teargas glistened with queer Molotov glow.

And on the computer, another fresh horror. Live ammunition used in Kowloon. One person hit square in the chest. Alive or dead? Nobody knew. No further reports.

Civilization scrambled in a Rubik’s cube spin. We sat there, too stunned to reassemble the pieces.

The scene outside was nearly as swift as it was violent. The front line fell back. The action kept moving upstream, in a teargas blitz. An army of cops, dressed in black, cleared the path. More police cars than I’ve ever seen made up the rearguard.

Behind them was nothing, barren streets of dystopia. Sooty skies and smoldering sidewalks. No one left to put out the fire that had started to creep toward the gas station.

The noises of discord faded steadily East. We looked around the room at each other, still processing.

Even my new friend’s friend seemed shaken.

‘Really nice hotel here,’ he said finally.

An hour or so later, we surveyed the ruin. The fever had mostly broken by then but the night was still hot, thick with sweltering pollution that clung to the day’s toxic fumes.

Potholes pockmarked ash-slicked sidewalks. Broken glass shroud the steaming street. Not one inch of wallspace was spared from graffiti. Bricks and empty teargas canisters led a breadcrumb trail of dissent all the way down to Causeway Bay.

The leftbehind garbage of panic and revolt fell at our feet, a flurry of paper masks and protest pamphlets and umbrellas. More paper money blew in with the wind. For the death of Chinese rule, and maybe some innocence lost.

People heavy with caution and curiosity wandered the empty streets in apocalypse daze. Eyes wide but not seeing, or at least not believing.

The dead-stopped heart of a world-class city. Did my friends think this scene represented the pinnacle?

I don’t see how that’s possible, they said. The stakes were much too high now for either side to back down. Not freely or willingly, anyway.

‘How does this all end then?’ I said. A question I had asked countless times that week.

We stared out at the devastation, not knowing the answer.

History repeatedly teaches us that freedom is not free.

LikeLike

Wow, Bridget. Thank you for living this. Thank you for having the courage to do so. This vivid and naked account told with such vigor has reminded me of the constant human plight that is so often silenced. I’m inspired by their (and your) capacity for courage, passion, and relentlessness.

I absolutely love the concept of flowing like water. It’s incredible how much wisdom there can be within resistance and even violence. I’m not sure how that revelation makes me feel, but it is definitely a new way of seeing.

Again thank you for living this life in a way the rest of us cannot. And for bringing me into a world so removed from my daily life. Yet definitely more connected than it seems.

Please keep going and sharing and staying safe!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the beautiful words, Jenna! ❤ It is truly incredible what the world can teach us, even (and maybe even especially) in times and places of plight. Hopefully, we can all learn the lessons and all flow together one day in harmony…

LikeLike

Wow, Bridget. Thank you for living this. Thank you for this vivid and unadulterated account. I am inspired by their (and your) courage, passion, and relentlessness.

I am so intrigued by the concept of flowing like water. It illustrates how much wisdom can live inside resistance and even violence. I’m not sure how I feel about this revelation, but it is certainly a new way of seeing.

I am also reminded of the constant human struggle, one that remains relatively silenced around here, but far from extinguished. I wonder about the circumstances that must occur for such a movement to rise up. I wonder about my own place in it all and if I’d be eating chips and salsa or wearing black.

Thank you doing what many of us cannot or will not. Thank you for providing a glimpse into a world so far (or seemingly far) removed from my daily life. I have such deep admiration for all you are doing.

Please keep going, keep sharing, and stay safe.

LikeLike

I would have much preferred this experience to have belonged to someone I had not given birth to–but your descriptions are vivid and vibrant and thrilling. Continue to observe–but from a distance!

LikeLike

Hahah sorry.. but for what it’s worth, I, personally, am pretty happy to be a person you’ve given birth to! 😉

Staying safe as possible always, promise!

LikeLike

Thank you for being like water…a concept you innately follow. We all learn and benefit from your experiences and words … you encourage our thoughts to be like water, if not our actions. You are brave, bright and empathetic to the people of the world…you walk the walk…fluidly❤️ Bravo and thank you Bridget!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for all the kind words of belief! ❤ It felt like such a monumental task to capture this movement in something as opaque as written language.. but I love their message too, and hope the lesson can continue to be passed on. It’s certainly a worthy one.

LikeLike